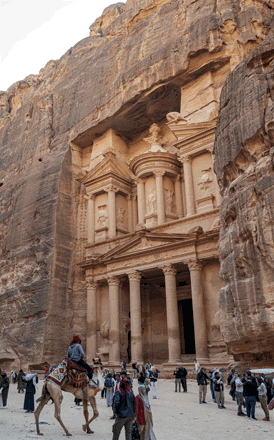

“Here, this is the gateway to the monastery, the most beautiful and famous monument of Petra,” said Abraham Mashaleh, 48, a Jordanian native born and raised in Petra who has worked as a guide to the ancient city for over 20 years.

He pointed at the narrow passage after a kilometre-long trail through rose-red “siq,” or winding rock gorges soaring over 100 metres up into the sky. “Yalla, yalla!” (‘Let’s go’ in Arabic), he added.

With a facade of 30 metres wide and 43 metres high, the monastery, or Ad Deir in Arabic, revealed itself as the valley slowly but surely opened up. Carved out of the rock in the early first century, the grand monument was the tomb of Nabataean King Areta IV and his son Malco II and represents the genius of the engineering of the ancient people, according to Mashaleh.

“Petra,” which in Greek means rock, is the ancient capital city of the Arabian nomads known as the Nabataeans, who built it more than 2,000 years ago in the middle of an extensive, arid desert in southern Jordan. Located three hours south of the Jordanian capital Amman and between the Red Sea and the Dead Sea, the prehistoric rock-cut city is one of the most famous archaeological sites in the world.

Its exotic landscape, which is authentically ancient and otherworldly, has often seen Petra being used in Hollywood’s cinematic productions for decades. It was the mysterious archaeological town for a treasure hunt in Steven Spielberg’s “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade” in 1989 and also the setting in Guy Ritchie’s Disney live-action remake of “Aladdin”, released in 2019, starring Will Smith as Genie.

Apart from its unique geology, the ancient city holds secrets and mysteries of the lesser-known ancient civilisation, for which it became a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1985 and one of the New Seven Wonders of the World in 2007.

According to Mashaleh, the ancient Nabataean people, who built and settled in Petra, were master builders of hydraulic engineering as well as successful desert traders.

“Now what we see is something else, something genius,” the guide said, pointing at the rock-cut water channel along the side of the winding canyons of mountains. “These are aqueducts, which provided water for irrigations (of crops). Other ones you’re going to see further on were for people’s drinking water, which came from all the way down to the city itself,” he said.

The city’s hydraulic engineering system was the Nabataeans’ key to survival and settlement in an arid area. The underground pipes and rock-cut channels are carefully designed and systematically placed to collect and carry rain and spring water to key points in the city and surrounding area, safe from evaporation and enemy invasion.

From the water management system, which is still used by local Bedouins today, the Nabataeans were able to feed their people and livestock, as well as to water crops, fields, gardens and grow olives, grapes, grains and pomegranates in the desert city.

The Nabataeans also made Petra the trade crossroads and cultural centre between ancient civilisations.

Located midway between Arabia, Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea, the city prospered as a key trading centre for incense coming from the Arabian Peninsula, silk from China, spices from India, and wine and metal from Greece and Rome 2,000 years ago. The commercial and cultural exchange of diverse civilisations in Petra can still be found in the city as its architecture shows how Eastern traditions blended with Hellenistic styles.

The Nabataeans were lovers of beauty and art too, and the archaeological relics unearthed in the ancient city show this in abundance. In prehistoric times, the Arab tribe made a wide array of elaborate jewellery out of gold, silver, bronze and iron, perfumes bottled in ceramics as well as textiles out of goat and camel hair. The region even had a vast amount of grape cultivation and wine production, the guide explained.

At its peak, the city housed as many as 30,000 residents, who even created their own script, which later became the basis of the Arabic alphabet.

“The exact reason for the city’s fall is not exactly known,” the guide said, explaining that the ancient city’s prosperous days eventually came to an end partly due to an earthquake in 363 and Arab conquest around 663.

--

Source: the Jordan Times.